|

July 25

Once again we heard lions calling

in the night; it is my abiding impression of the essence of

Africa. We were on the road early again, watching a rose sky at

dawn, the rising sun reflected in the water.

We stopped to watch some francolin

chicks scurrying across the road behind their mother; or were they

spurfowl? I was still a little confused on the difference;

something like francolins are considered spurfowl, but not all spurfowl are francolins

- or was it the other way around?

As we were contemplating these birds, suddenly Jineen

looked over in the other direction and spotted a honey badger.

Unbelievable! It was

near where we had seen one the night before; most likely it was

the same fellow. This time he was much closer, and we got to watch

him as he snuffled around, looking for food.

|

Honey

badger

|

Gee told us that the honey badger, also known as the ratel,

is very tough and hard to kill. His bones are elastic

because they are made of cartilage;

you can run a jeep over him and he is still all right. He can

withstand bee stings and snake venom without harm. Honey badgers

are very fierce, and the other animals fear them. Gee said a honey

badger will never give up. However, if you hit one on the nose, it

will faint. He was chased by them many times as a boy growing up

on the island.

It reminded me of that honey

badger video on the internet: “That

crazy nastyass honey badger. Honey badger don’t care. He

doesn’t give a s#*t.

Our honey badger was scratching through the grass and

leaves, sniffing for food. He started to dig purposefully,

crouching down and using his strong front claws, throwing up a

shower of dirt and dust. Soon he had his head and shoulders down

in the hole, his body curved like a ribbon. From time to time he

would stop and look up at us suspiciously, and then dig some

more.

He caught an earthworm snake and

ate it; we could see the pink strands of it hanging out of his

mouth as he chewed. He raised his head and looked at us, sniffed

warily, and moved on to dig another hole; this time he found a

frog, and quickly devoured it. Honey badger don’t care. Ooh,

that’s nasty!”

|

Eating an earthworm

snake

|

Finally

the honey badger moved off, and we did too. We came out by a large

lagoon; a huge mother hippopotamus floated in the water, and

nearby was her small baby, just several months old, hanging out

with a half-grown female who was probably her older sister.

Several others were sleeping along the shore. We could see

scratches and scars all over the big mothers’ back. The older

sister yawned expansively, showing massive incisors, and then

gently snuggled with the baby. There was a partially decayed

elephant carcass in the edge of the lagoon; I tried to avoid

looking at it.

Fred the bushbaby was getting a lot of attention; we passed

another safari vehicle, and when the occupants spotted Fred they

wanted to take selfies with him. I think Duma the baby cheetah was

a little jealous. One of the men told us they had made up a song

to help them find bushbabies. With a bit of urging he sang it for

us; it was to the tune of Matchmaker

from Fiddler on the Roof. He started singing, “Bushbaby, bushbaby . . .

“ I can’t remember

the rest of the words, but surely every bushbaby in the area would

flock to them if they sang that on a night drive.

We drove on, ever in wonder at the

nature all around us. A fish eagle and three vultures perched high

in the same tree. A whole flock of red-billed quelea flew up in

front of us; these were the birds we heard the first evening in

Khwai making chattering cricket-like noise. We saw some zebra and

a couple of ellies, and a jackal in the distance. A lame impala

hobbled across the plain; we figured he would soon be somebody’s

dinner. Gee found a spot he liked and parked the Landcruiser, and

we all got out. We were going for a walk.

Walking safaris were allowed in Khwai, unlike the national

parks. Gee carried a rifle over his shoulder as the rules

required; he had borrowed it for this occasion. He told us to stay

close to him in a line, and he gave us the usual safari

instructions in case we encountered a dangerous animal: Whatever

you do, don’t run!

A walking safari has a different

focus than game driving; it is not a time to try and see large

animals or predators, but rather a chance to observe close-up the

little things that you miss when in the vehicle. We put our

attention on such things as plants, insects, tracks and animal

dung.

|

Walking Safari with

Gee

|

We followed Gee across the plain. He was alert, taking our

safety very seriously, scanning the open areas for elephants and

lions constantly. He pointed out different plants and herbs,

telling us of their uses. Cat’s claw for family planning, he

told us; one cup of cat’s claw tea prevents pregnancy for 15

days. He showed us pepper pen plant, which can be used to get rid

of an unwanted pregnancy. I particularly liked the pretty little

curlicue plants that looked like tiny valentines, known as

crowfoot grass.

Remembering hearing about in the past, I asked Gee about

the magic gwarri bush, also known as the toothbrush tree. People

use the roots from this shrub to clean their teeth. Gee said that

he didn’t see any at the moment, but later he would find us a

toothbrush tree so we could try brushing our teeth with it.

Gee examined some elephant dung,

estimating how old it was by the moisture content. It was filled

with large twigs and sticks; the elephants only digest 40% of what

they eat. He told us that if you gathered elephant dung, you could

sell in the city; it is full of many undigested plants and herbs

that are thought to bring strength. People mix it with the fat of

a snake or a lion to protect a newborn baby; they put this mixture

on coals to ‘smoke’ the child, calling on the spirits to

protect the baby from witchcraft. Any bad spirits will see the

lion and elephant spirit in the child, and he will be strong and

safe.

Everywhere we saw wide paths crisscrossing through the

bush, covered with the oval footprints of elephants. Gee called

them elephant highways, and showed us how to interpret them. The

prints are smooth at the back and often have scuff marks on the

front; this is how you can tell which way they were going. When

the elephants are walking quietly, the hind prints are right on

top of the front, like a horse ‘tracking up.’ When they are

running, the hind oval would be well in front of the round front

track. Gee showed us a fresh print, the wrinkles on the bottom of

the elephant’s foot etched clearly in the dusty path; he then

sprinkled sand over the track several times, to show us what it

would look like in a few hours, and in a few days. We also

examined many other tracks, everything from mice to springhares to

impala, to see what had passed this way; this is called reading

the daily news.

Gee kept a constant lookout for dangerous animals,

especially elephants, and explained to us how to find the safe

areas to walk. He showed us an elephant’s bed, an area of

flattened earth with dug-up tusk marks on the ground made from

when it stood up. He said elephants mostly sleep standing up,

especially the mothers, but the youngsters like to like down, and

the bulls do also for short periods.

|

Gee Mange

|

We heard the harsh bark of an

impala alarm call. There was a small herd of the antelopes nearby,

with heads up, staring warily. The impala alarm usually means a

predator so I looked around for a leopard or lion, but then I

realized they were snorting at us – they don’t see us as a

threat when we are in the vehicle, but when we are on foot they

do.

Gee showed us several types of

fresh dung, and quizzed us on what animal had made it. Hyena dung

is green when fresh, but turns white when it dries from the

calcium in all the bones they eat. The tortoises will eat hyena

dung for the calcium it provides. We found some furry turds with a

lot of hair in them, left by a leopard. Springhare dung is pale in

color; Gee told us they eat their own dung. I would rather not

have known that . . .

We stopped beside a large hollow stump; Gee cautioned us

not to reach into it (not that we were considering it!), as there

could be a snake inside, or a leopard might have hidden her baby

there. We sat on a fallen log and took a short break before

heading back to the Landcruiser.

|

Patty and Rob

|

We never went far without seeing something interesting. We

drove past a herd of zebras, with one youngster lying down taking

a nap. Gee spotted two green wood hoopoes in a tree. A pink-backed

pelican floated on a pond and a white-winged tern bathed in the

shallows.

We stopped for tea beside a

flooded river with many marshy channels. Drowned trees stuck up

out of the water, and a few lilypads floated near the edge. It was

a particularly beautiful spot. There was a herd of waterbucks on

the other side, mostly females and youngsters, with one grand old

buck.

|

Waterbucks

leaping a channel |

At first the waterbucks were grazing peacefully, but then

they began milling about restlessly, turning their target-marked

rumps toward us. It became evident that they wanted to cross the

river. They all lined up and started moving in a single file row

across in front of us. They splashed through the water, and then

one after another, they leaped spectacularly across the deeper

channels of the river. The females and youngsters went first, and

the buck brought up the rear.

Gee

talked about some of the local cultural beliefs and customs, and

told us a little about the people’s belief in witches, wizards

and witch doctors. He told us this story about his friend’s

brother, Moses:

‘Moses wanted to be a prophet,

so he would have much power. There was an old man in Zambia, a

witch doctor, who could give him this power, but it required Moses

to choose one close family memory to sacrifice. He was willing to

do this, but he needed money to pay the witch doctor. He tried to

borrow money from his brother, he tried to borrow money from me,

and from everyone he knew. He tried to raise the money by getting

his parents to sell some land, or by stealing cattle to sell.

Nobody would help him get the money to become a prophet.

Moses’ brother is a good friend,

and he came to me for help. “Moses needs to sacrifice a close

family member,” he said. “It might be me! Or it may be our

mother, or our sister - we must stop him!” They went to his

parents’ house to try to talk to Moses. The whole family met,

and the brother told everyone of Moses’ plan. Everyone wanted to

know - who would he sacrifice? Moses denied it all, but no one

would give him the money. He went away, and later came back as a

low-level prophet, wearing lots of beads. But he never got the

power that he wanted.’

Traditional healers, or sangomas,

which we would call witch doctors, are still a big part of the

culture in Botswana. If you get sick or your cattle die, maybe

somebody cast an evil spell on you. You would go to a witch doctor

to get that spell taken off. Or you might pay a sangoma

to put a spell on your enemy, calling on the evil spirits. It all

seems very strange to us, but when you are there in Botswana and

hear the stories firsthand - well, anything seems possible.

As we continued on we saw another Letaka group, and we

watched as a huge bull elephant with enormous crooked tusks walked

slowly by their Landcruiser, passing within inches. It was

interesting to observe how small the Landcruisers are compared to

the elephants. Gee handed the rifle over to the other guide, who

needed it to take his clients walking.

As we drove back along the river, all of the usuals were

about; kudus under the trees, impalas in the sunlight and a family

of zebras across the river. A kudu and an impala grazed together,

the size difference making them look like mother and baby. We

passed a huge black mamba hotel, about four meters tall. Gee said

this termite mound was probably about 60 years old; it is about

ten years for every meter in height, but this one used to be

taller before being eroded away.

We saw a prickly yellow and orange

fruit, somewhat cactus-like; Gee said it was a wild cucumber.

Ostriches and porcupines get their water from eating these, like

summer melons. Ostriches do not need to drink water; they get

enough from the fruit.

Gee pointed out some plants with

round ball-like blooms which he called African Daga (pronounced Da

Ha); he said it is a natural marijuana plant, and you can smoke

the leaves or the balls. Jineen and Patty discussed plans for

collection and harvest.

We saw a great many birds along the river. A pied

kingfisher perched on a thornbush, and a long-toed lapwing guarded

her nest in the grass. Only the snakelike head and neck of a

darter was visible above the water as it swam downstream. We saw a

glossy ibis, similar to the hadada, with shimmery green on its

wings. A grey-backed camaroptera, sometimes known as a bleating

warbler, flitted through the bushes. A squacco heron flew along

over the river, and a spur-winged goose waded in the shallow

water. A beautiful coppery-tailed coucal stood in the grass,

gazing up at us with his bright red eyes.

|

Coppery-tailed

coucal |

A hamerkop came gliding in for a landing, then waded into a

shallow water channel. These medium-sized brown birds have a

hammer-shaped head and a sturdy build. They are a rather drab

muddy brown color, and are somehow a bit prehistoric-looking. They

are interesting looking more than handsome – and yet there is

something about them I find really appealing. The hamerkop steals

clothes, shoes, and whatever else it can find to build huge

elaborate nests.

|

Hamerkop

|

A goliath heron stood in the reeds, and as we approached it

rose up and flew away on slow motion wings. It is an elegant slate

grey bird with mottled rufous and white markings on its neck and

underside. The world’s largest heron, the goliath is an

endangered species. We caught up with it again at the next bend in

the river for a closer look. A Nile crocodile lurked among the

lilypads, clean and brown with pale green eyes.

|

Goliath heron |

Heading back to camp, a herd of female impalas ran across

the road in front of us, tightly packed together, alarmed at

something. Then they stopped and milled about, apparently

forgetting about whatever danger they had perceived. We admired

their elegant refined faces and big dark eyes; it is easy to take

the impala for granted because they are so common, but they really

are quite beautiful.

Phillimon greeted us with the usual goblets of sweet bush

tea; I would have to remember to get the recipe for that tea! We

had cheeseburgers for lunch, and then relaxed and enjoyed the

view. I could see the lagoon from my tent window, and the dining

table was right beside the water. The Landcruiser was parked

nearby. The kitchen and staff tents were a little ways off and we

stayed out of that area to respect their privacy, but Phillimon

stood on a termite mound and waved to us.

|

Phillimon

|

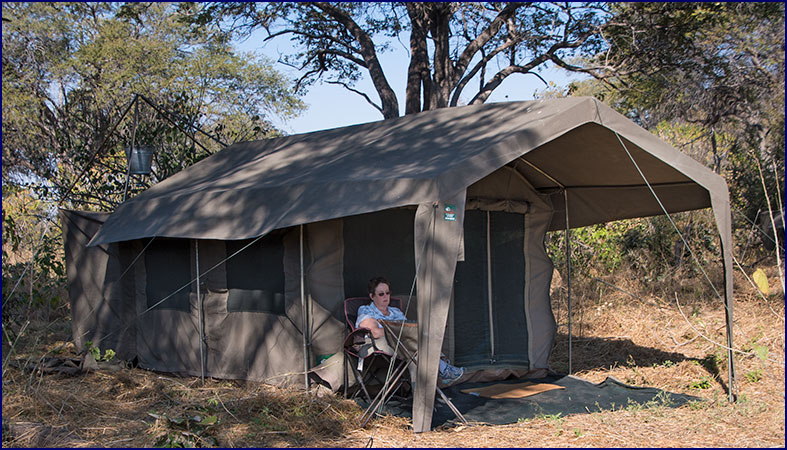

I took some photos around camp. Sadly, my Coolpix camera

was dead; it would no longer work after being dropped the previous

day - a blacksmith plover down by the river was the last photo it

would take. I would miss having that zoom lens for the rest of the

trip; it was not my best quality camera, but it did have the

greatest telephoto range.

Paula at her tent

|

As we were just heading out on the afternoon drive we heard

loud crashing noises; an elephant came through the edge of the

camp, noisily breaking branches off the trees. Rob said it sounded

like giants walking in a forest. There was a big warthog just

outside camp; he turned and showed us his backside. A bit further

on a beautiful female red-crested korhaan walked through the

underbrush; she had long legs, large eyes and variegated brown,

black and white plumage.

We were driving through the woods when suddenly there were

elephants all around us, moving through scrubby trees barely

taller than they were. It was a breeding herd, and the mothers

were shielding the smaller babies from view. We stopped to let

them pass, and within a few minutes, they had all disappeared into

the trees. It is amazing how one moment there can be a dozen

elephants in full view, and a few seconds later they have vanished

without a trace.

The herd came back into view and began to feed, and we sat

and watched them. The elephants would break off a branch and eat

it, then go to another tree and repeat the process. Tara asked why

they kept moving so much; Gee explained that when the elephants

start to eat, the tree releases a bad-tasting tannin for

protection, so the ellies move on to the next tree.

A dainty steenbok stood in the yellow grass; he was a

delicate, exquisite creature. He had big ears, sharp straight

horns and a petite refined face. He seemed like a creature out of

a story book; one wasn’t quite sure if he was real.

|

Steenbok |

A bit further on we paused to watch an elephant taking a

dust bath - but he came out of the dust wallow and moved toward us

aggressively; Gee said he was in musth, and drove off quickly. A

few minutes later we came across yet another angry bull elephant;

he was striding angrily in front of us, stomping up great clouds

of dust. He was looking for females and seemed very bad tempered.

Another musth fellow? It must be something in the water! We

yielded the right of way to him.

We were hoping to see some cape buffalo, but the closest we

got was a cape turtle dove. These handsome birds are a pale

greyish-brown color with a tinge of pink, and have a black ring

around the back of their necks. They can often be heard making a

repeating chant-like call; it always sounds to me like they are

calling Bots-wa-na, Bots-wa-na.

But Gee has another interpretation; he says in the morning

they are calling work hard-er, work hard-er, but in the evening they switch to drink

lag-er, drink lag-er.

|

Cape turtle dove |

We

saw a couple more new birds; a brilliantly speckled groundscraper

thrush and a tiny rattling cisticola. Rob was very intrigued by

some spider nests in the trees, made from very dense web. And a

couple of my favorite birds were there; a pair of brilliantly

colored little bee-eaters sat on a twig, and a Burchell’s

starling perched on top of a tree, glistening blue in the sun.

|

Little bee-eaters

|

We stopped to check out the hyena den; one adult female was

stretched out on the ground by the entrance. Gee said she was a

mother; we waited, hoping the babies would come out of the den.

The hyena looked like she was fast asleep, but when we approached

she opened her eyes and looked at us with a keen expression.

We sat watching her for a while,

and also looking around at the surroundings. Gee pointed out a

tree with pointy knobs all over the trunk called a knobthorn

acacia. The meadow was filled with beautiful golden grasses that

took on the shape of feathery ferns and delicate curlicues.

Gee told us that hyenas steal dens

from aardvarks, and then the warthogs will steal them from the

hyenas. He said that hyenas are primarily scavengers, though they

will also hunt if needed. I loved the way Gee pronounced

scavengers with the accent on the middle syllable: Sca-VEN-gers

(like avengers). The

hyena briefly raised her head for a moment and looked around

lazily, then flopped back down on her side again. We left her

slumbering.

Gee pointed out several toothbrush trees, but he said these

were too large; it is better to use the roots of smaller shrubs so

they aren't too big and tough. He promised to find us some the

next day, so we could brush our teeth the traditional way.

A business of nine dwarf mongooses

climbed on top of an old termite hill; half a dozen youngsters

played on the top while several adults kept watch. One of the

sentinels stood on its hind legs watching us closely. Would the

plural be mongooses, or mongeese?

|

Kudu

doe at sunset |

Entering a wooded area, there were two beautiful female

kudus. One was surrounded by tall grass, and the other stood on a

termite mound beneath a large tree. The late afternoon sun bathed

them in delicate light, and I felt like we were in an enchanted

forest. Just as the light was beginning to fade, the kudu bull

came walking out of the trees. He had towering spiral horns and a

terrific mane beneath his neck. It was beautiful, surreal; they

were like dream kudus, surely magical.

We watched the sun lowering between the trees, turning the

sky to crimson and orange. Then we went out onto the floodplain;

four lechwe stood bathed in red-gold light, and an elephant ambled

across in the background.

We stopped for Sundowners beside a

huge lagoon. The sky, fiery red near the sun, faded from magenta

to dusky rose to a deep blue above. As the huge disc of the sun

slipped below the horizon, a colony of egrets perched in a bare

tree were silhouetted against the red sky. We could just make out

the dark forms of crocodiles along the edge of the water.

As the sky darkened we could see the crescent moon, just

barely thicker than the night before, still hanging horizontal

like a smile; we couldn’t remember ever seeing it in quite that

position at home. The brilliant colors along the horizon lasted

long after the sun had slipped away.

We stood by the vehicle, sipping a

glass of wine and enjoying the peaceful evening. We could hear

elephants trumpeting and splashing, and hippos honking in the

night. Gee passed around a Sundowners snack; chunks of banana

wrapped in bacon – they were surprisingly good.

Night falls quickly in Africa;

near the poles the sun moves more horizontally through the sky

(think of how it barely dips below the horizon in Alaska in

summer), but near the equator it drops straight down, going from

daylight to dark very quickly.

As we began packing up, Paula said “Don’t leave me”

and made a quick trip behind a bush. This turned the conversation

to what would happen if we were

left out there. If somehow Gee took off and left us at the lagoon

for the night, would we survive, or end up as somebody’s dinner?

Fortunately we did not have to put it to the test.

It was pitch dark as we headed back to camp. An

elephant was in the water where the road forded a stream; as we

waited for him to cross, Gee carefully averted the spotlight,saying the elephant would be angry if we shined it in his eyes. We

passed close to a grazing hippo – this was the nearest we had

been to one out of the water. Gee said they can weight up to 2 ½

tons. We saw more springhares; I never get enough of them.

Gee stopped the Landcruiser and we

sat and listened to the night sounds – always one of my favorite

parts of the night drives. Gee told us a story from his childhood

about being left alone on his family’s island. His parents went

to town in the mokoro to sell palm wine, but they got drunk and

didn’t come home until after midnight. He was quite young at the

time, and he was responsible for taking care of his younger

siblings. When it got dark and his parents had not come back, he

became quite scared. He could hear jackals, owls, hippos. Were bad

spirits coming? He did not know what to do. Finally he could hear

his parents singing as they came back to the island in the mokoro.

After that is when he got to know the bush; he learned all about

the animals and how to get around safely in the wild. That is the

difference between Gee and the other guides; he grew up in the

bush, and knows it in a way that few do.

We

had fish and chips for dinner; not exactly the meal you expect to

be served in the wilds of Africa, but it was excellent. We were

constantly amazed at what Pula and the others could cook using

camp stoves and Dutch ovens. Around the campfire we could hear

trumpeting elephants for a long time - must be another bull in

musth.

|